news

Rewards and the right way to use them

Posted on July 10, 2018

By Lisa Hannaford, Psychologist, OAC Student Wellbeing Team

While some students find their niche and love to learn and make things, the reality for some students is that they are not motivated by some/all school activities and are seen by the adults in their lives to be passive, uninterested, listless and reactive (rather than proactive).

So…what motivates children and young people to not only enjoy what they’re doing, but to flourish as a person?

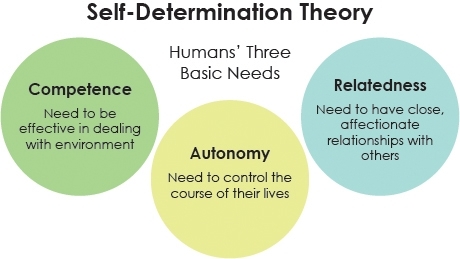

According to Self-Determination Theory we have three psychological needs and when these are met in the classroom, at home with the family, or in other social contexts, we have the greatest chance to learn and grow.

They also foster self-motivation, behaviour regulation and positive personality development. These essential needs are illustrated and described below:

1. The need for Competence:

I can do this and I know this because adult feedback tells me I have ability and am improving

I enjoyed observing a year 1 teacher respond to a student who was complaining that her peer was doing it “all wrong”. The teacher said, “Sarah is a competent, capable learner who can do this on her own” and walked away. This is a powerful message for an adult to give both children in this situation. Sarah was doing it wrong but as teachers often tell their students, there’s no learning without mistakes.

If the teacher had rushed in to rescue Sarah and problem solved this conflict, then the message would have been received by both children as “Kylie is right, you can’t do this on your own Sarah and you will need to rely on me to succeed as a learner.” But what to do when the student is just beginning out in a task and doesn’t yet have competence? The answer lies in motivation.

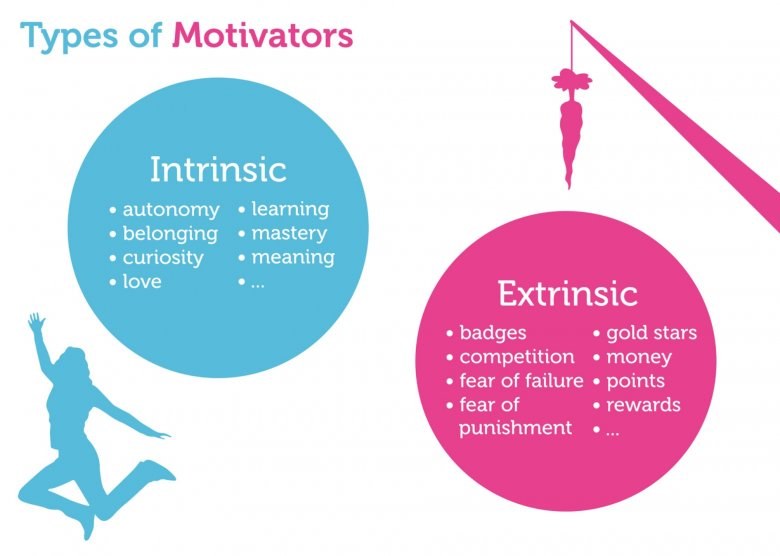

There are two types of motivation, intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.

Image Courtest Eric Delcroix, via Flickr

The term extrinsic motivation is when students perform an activity in order to get something desirable, in contrast with intrinsic motivation which refers to doing an activity for the inherent satisfaction of the activity itself.

Many learners require extrinsic motivation in order to reach the stage of competence needed to derive enjoyment from an activity. For example, people who read for pleasure do so once they have reached a level of mastery in reading. People struggling to read do not tend to engage in reading in their downtime and may need external motivators to practise reading.

Once they have developed reading skills, motivators can be withdrawn and the student can read with enough skill to find it enjoyable (intrinsically motivating).

2. The need for Autonomy:

I got to choose, I helped determine what I’m doing, I had a voice in this system

In Self-Determination Theory, Autonomy refers to the need to control the course of one’s own life. This is more than independence; it is about having a sense of free will and making choices that align with our interests and values.

Studies have shown that when parents and teachers support autonomy in children, it is more likely to enhance intrinsic motivation, curiosity and a desire for challenge. Research shows that a controlling approach can result in a loss of initiative and less effective learning overall, especially when learning requires conceptual, creative processing.

How you give children and young people a sense of autonomy depends on the child’s developmental abilities and each situation. Autonomy can include allowing the child to pick topics, new areas to explore, the best time they like to do things, and so on.

But, I can hear you thinking, I’m the adult and I need my child to do what I say. And I would agree with you. However, as the saying goes, children vote with their feet (and mouths!). Adult rules and instructions are crucial. They provide consistent boundaries that ultimately give a child a sense of safety.

But when adults tap into a child’s need for autonomy and independence, then they will have a child who is more likely to flourish (and follow instructions) because they feel self-determining.

For example, chores have to get done but you can give the child a sense of autonomy by allowing them to select from a menu of chores or what time of day they want to do the chores, or which cleaning tools and products they like to use (thereby giving them the illusion of choice and sense of autonomy). Adults can also use negotiation where possible/appropriate.

3. The need for Relatedness:

I belong, and nice things I do make it better for this group I belong to

Relatedness in this sense refers to the caring connection a child or young person has with the people in their lives, which in turn leads to a feeling of belonging. Jennifer Payne is a psychologist and director of Rypple, a W.A. non-profit organisation using evidence-based positive interventions to improve social culture, behavior and mental health for young people in schools.

Ms Payne states that “relatedness has been found to be the most powerful factor to increase the degree of self regulation of behaviour”. That is, students who feel connected to adults are more likely to behave better, and be more independent in controlling their own behaviour.

In her practise, she therefore employs social rewards alongside rewards for the individual, such as whole class and school prizes/activities. Whenever rewards are given, adults explicitly label the desired behaviour the adult is trying to reinforce in the group and/or the individual.

Ms Payne provided this stand-out example in her presentation at the 2017 APACS conference. The pictured negotiated reward (i.e. students brainstormed ideas for rewards and adults approved them) was for a group of students to gaffa tape the-genuinely smiling-principal to a pole in the yard.

Picture courtesy Rypple: Fitzroy Valley District High School used social rewards to achieve positive behaviours in a group of students.

Now this might be a step too far for some, but it illustrates wonderfully how a fun approach to group rewards can yield days/weeks/months of great behaviour and increased learning. Reward systems that positively reinforce the behaviour of one chid/young person are powerful, but rewards which move a group towards a shared goal seem to be even more powerful.

More Information

This useful parent’s account of using rewards for her son, and her research into when rewards are helpful and when they aren’t, can be found here. For further reading on Self Determination Theory and rewards, the below articles may interest:

- Deci, E. L. (1975). Intrinsic motivation. New York: Plenum.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000) Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations: Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology 25, 54–67.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68-78. (available here: https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/SDT/documents/2000_RyanDeci_SDT.pdf)